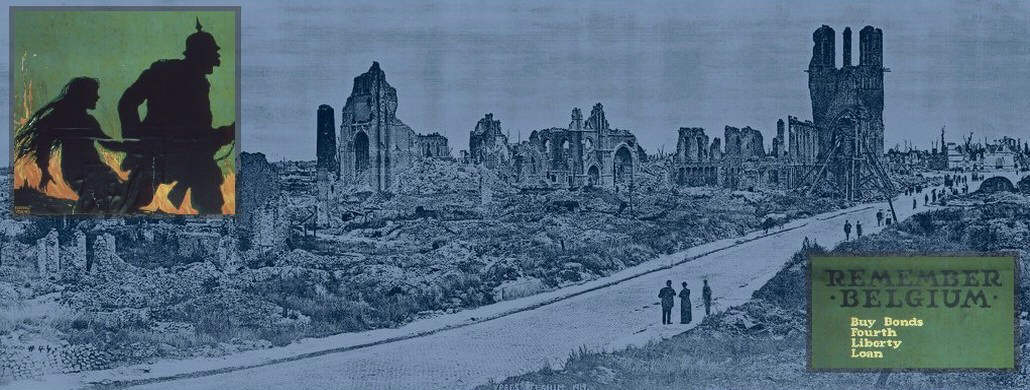

[USA, 1917/18] Horrified, Lorenz Bergmann’s granddaughter Chiara looked at the Liberty Bonds she was about to buy. It showed a creature with a Pickelhaube, thus obviously a German.

It was completely dehumanized, and even a gorilla didn’t look like that. More like how one imagined the monsters from scary movies. “Halt the Hun!” she read, and on another, “Remember Belgium.” But this “Hun” had nothing in common with her beloved grandfather, Lorenz Bergmann, who had come to the United States from Germany so many years ago. So she German ancestors, and throughout her childhood she had collected pictures of her grandfather’s distant homeland. Chiara would have loved to go there herself, but that seemed impossible now.

Public opinion turns against Germany

The United States under President Woodrow Wilson had so far remained neutral. On the contrary, in the 1916 election campaign, the slogan: “He kept us out of war!” had won many people over to Wilson. Certainly, the democratic United States had more sympathy for the democratic governments of England and France. A major concern of President Wilson was the right of nations to self-determination. At the start of the war, the Entente powers had taken out war bonds in the U.S., and exports to England and France by sea had increased threefold.

But in the meantime, a lot had happened. Since the German army had invaded neutral Belgium, horrific reports of their brutality had been circulating Herbert Hoover (later U.S. President), founded the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which contributed significantly to the survival of the civilian population with food aid. In Great Britain, advertising posters appeared, saying that the Germans were raging “like the Huns”. In the USA, public mood was turning against Germany.

Then on May 7, 1915, the British passenger ship RMS Lusitania was hit by a German U-boat torpedo and sank. Among the victims were American citizens. The U.S. had protested sharply and threatened to enter the war.

Unrestricted submarine warfare

By early 1917, Russia was at the brick of revolution. That was good news to the German High Command, since it would take Russia out of the war. The prospects for the Allies darkened, those for Germany brightened, as more forces would be available for the Western Front. They could break the devastating army stalemate and finally defeat the Allies. However, the British naval blockade threatened to starve Germany into collapse.

Germany’s mightiest weapon was the U-boat fleet, to be precise U-boats operating without any restrictions. Military and political leaders were aware this would probably trigger the USA’s declaration of war. However, they were sure they could force Britain down before U.S. troops would arrive in Europe and engage in combat. In the meantime, the generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff had taken over the High Command. Both of them wanted a military victory, along with the Admiralty they opted for unrestricted submarine warfare. Soon Hindenburg and Ludendorff got their way. Overruling chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg’s warnings, Kaiser Wilhelm II agreed that from February 1 onwards, submarine warfare should be unrestricted and overtly so. In other words: U-boats had permission to sink without warning all ships except passenger vessels.

President Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Germany on February 3, 1917, and asked Congress for arming merchant ships and all measures that were necessary to protect U.S. Commerce. Yet he stopped short of declaring war. He adhered to a policy of “armed neutrality” and declared that the United States would no go to war in the absence of an “overt act.”

Zimmermann telegram

On March 1, 1917, the American public learned about a German offer to Mexico to side up against the USA. In mid-January 1917, the British intelligence had intercepted an encrypted telegram from Arthur Zimmermann, Undersecretary of State in the Foreign Office, to the German envoy in Mexico. Even the first decrypted passages were explosive: Germany intended to start unrestricted submarine warfare on the first of February. It still wanted to keep America neutral. If this did not succeed, Germany offered the government of Mexico an alliance to regain the territory lost to the United States in 1848. The British intelligence delivered it on February 23 to American Ambassador Walter Hines Page in London, and onFebruary 28, it got to President Wilson.

On April 1, the New York Times reported on the German offer and published the text of the dispatch. This outraged the president and the public alike; from now on, the German government was trusted with everything. The fact that Zimmermann’s offer of an alliance against the United States had gone over the latter’s own cable, left in confidence, outraged the United States even more.

A war to end all wars

The USA had just fought an almost guerilla war against Pancho Villa in Mexico. Across the nation, support grew for intervention. By the end of March, Wilson’s cabinet unanimously advised war. Economically, the Allies relied on US supplies and armaments, and loans to pay for it. By April, the Allies had no more financial ressources.

On April 2, President Wilson asked Congress to declare war against Germany specifically citing Germany’s renewed submarine policy as “a war against mankind. It is a war against all nations.” He also spoke about German spying inside the U.S. and the treachery of the Zimmermann Telegram. Wilson urged that “the world must be made safe for democracy”. On April 4, the Senate voted to declare war against Germany, on April 6, the House of Representatives passed the resolution.

A hard time for German-Americans

It was a hard time for German-Americans. It had been difficult during the last few years already, when the tide of public opinion was turning against Germany, Most of them remained neutral and opposed American arms shipments to Europe.

Now German Americans were harassed in many ways. Twenty-six states issued laws against the use of the German language. In some areas even teaching German was forbidden and German textbooks were burned. Under the Alien Enemies Act, Germans who lived in the USA were occasionally arrested and interned. German-Americans had to prove that they lived, thought and felt as US citizens, not as subjects of the Kaiser in faraway Germany.

Furthermore, the discussion about a nationwide ban on alcohol became increasingly political. German or Austrian immigrants ran most breweries in the USA. Although the wine industry was mainly in Italian-American hands, there were wine-makers of German descent too, like the Mountain Men vineyards in the Shenandoah Valley, her mother Amber’s home. Prohibition, a nationwide ban on alcohol, would endanger their existence too.

Mobilizing for war

President Wilson had declared war on Germany, the USA entered the Great War as an “Associated Power” to the Allies. As the USA had only a little army, a system of conscription was introduced by the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917, 2,8 million men were drafted. On May 26, Major General John J. Pershing was appointed as commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.)

However, the USA was ready for war. It would take many months to raise, train and bring the expeditionary force across the Atlantic to Europe. Besides, the army had almost no heavy artillery pieces, a small air service only, less than 500 machine guns, no tanks, and no steel helmets. Moreover, they had no equipment to protect the soldiers againt gas attacks. Eight hundred British and French combat veterans came to the U.S. to prepare the American troops for the grueling war at the Western Front. The new recruits struggled to keep their heads down while crawling under barbed wire. They learned they had seven seconds to put on a gas mask.

American Expeditionary Forces

Within a year of declaring war, the U.S. had assembled a military force of nearly 4 million men and women. The American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) combined units from the regular Army, Marines, various state National Guards nationalized by the federal government, and the new National Army created from volunteers and draftees.

From July 1917 the USA sent troops to Europe. Many families feared for their husbands, fathers, sons and brothers, and waited for news from the front in distant Europe. “Safer for Democracy” the world should be after the war, the USA fought for a just cause and for peace. So President Wilson had spoken on January 8, 1918, to the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Chiara and John

Chiara’s heart was heavy. She was not ready to let her beloved husband John go. “Many of my young men are already on their way to Europe,” he had said, “I cannot let them down.” All her thoughts were with him. And yet, they often wandered to her German relatives too. Sophie, Andras, Lottie, Matthias, and their children, the Bergmanns – what had happened to them? Were they still alive? She had got to know them as kind and open-minded people who had endured hardships for living their ideals of tolerance and liberty. She could not imagine that they were as brutal as “the Hun” and as megalomaniac as “The Kaiser”.

But why had Germany not responded to the “Fourteen Points” set out by President Wilson on January 8, 1918? Wilson wanted peace based on the “self-determination of peoples” without victors or conquered. Chiara could not know that “the Kaiser” had long time since been marginalized. Since Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg’s forced resignation in summer 1917, the Supreme Command, precisely General Ludendorff, had been determining German politics. De facto it was a military dictatorship. Hindenburg, Ludendorff and their Supreme Command outright rejected the “Fourteen Points”.

Be the first to comment